Reel Streaming

- andreasachs1

- Oct 29, 2020

- 5 min read

One film journalist’s stream-of-consciousness cinematic journey through the pandemic, Part 21

By Laurence Lerman

Six months ago (hell, it feels like six years), having offered up the pleasures of the all-star disaster epic The Towering Inferno on these pages, a friend suggested I take a look at 1952’s Ruby Gentry, starring Inferno featured player Jennifer Jones. The Southern-fried melodrama finds the five-time Oscar nominee Ms. Jones (who brought home the coveted Best Actress statue for 1944’s The Song of Bernadette) portraying a backwoods temptress who tries to sink her hooks into a former high school flame, played by Charlton Heston.

Well, I’m passing on Ruby Gentry once again, but not on the exquisite Ms. Jones—who starred in Vittorio De Sica’s 1953 romantic melodrama Indiscretion of an American Wife. I hoped De Sica’s partial dip into Hollywood’s filmmaking waters would provide a brief respite from the all-too-addling realism of these past weeks. And what better way to get away from it all than to dive into a film by Italy’s great neorealist? (Then again, they say everything old is new again, so who knows…?)

As is often the case with cinematic misfires, the story behind Indiscretion of an American Wife is more intriguing than the film itself.

An Italian-American co-production between De Sica and producer David O. Selznick (who commissioned the film as a vehicle for his then-wife Jennifer Jones) was reportedly troubled from the very beginning.Its deceptively simple story presents an American housewife (Jones) vacationing in Italy who decides to end her affair with an Italian academic (Montgomery Clift) while in Rome’s Stazione Termini.

A number of notable writers hired to write Indiscretion’s script were fired during the process, including Carson McCullers, Alberto Moravia, Paul Gallico and Truman Capote (who ultimately received the screen credit). Selznick would send lengthy letters to De Sica every day of the production, which took place on location at the large Rome train station. De Sica, who apparently didn’t read English, apparently agreed to everything Selznick wrote, but then did things his own way. The stars were said to be unhappy as well.

The first release of the film, which retained its original title of Terminal Station, ran 89 minutes and was coolly received during previews, prompting Selznick to re-edit it down to a lean 64 minutes and change the title to Indiscretion of an American Wife without De Sica’s permission. Neither the critics nor the moviegoing public much enjoyed either version, which isn’t surprising—the performances are good but the film is dull and only notable for G.R. Aldo’s crisp cinematography and young Richard Beymer smiling up a storm as Jones’ young nephew. (Beymer had even more to smile about a decade later as Tony in 1961’s beloved West Side Story.)

Another addled wife and mother—this one on New York’s Upper East Side—found herself dabbling in affairs extramarital in 1970’s Diary of a Mad Housewife, a hard-to-find title for years that was recently released to streaming platforms for the first time.

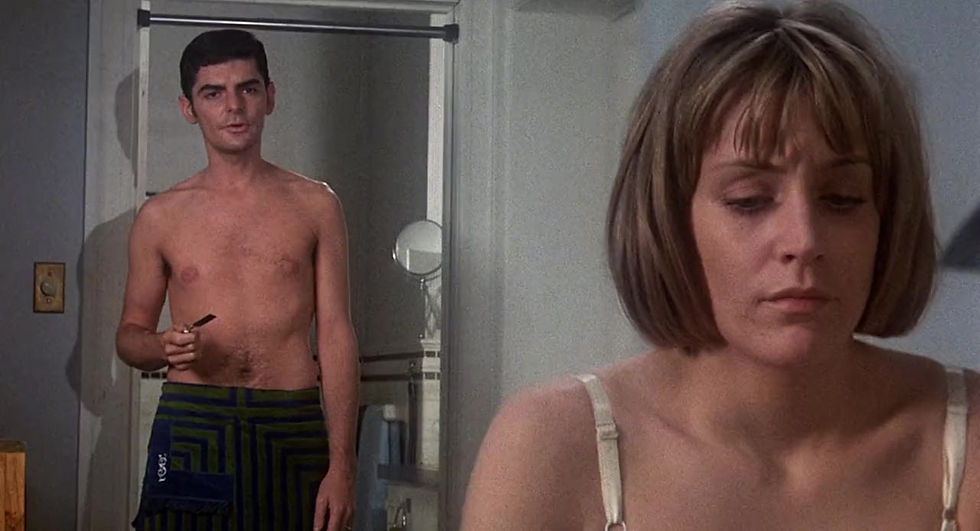

Diary centers on lovely Bettina Balser (Carrie Snodgress), an anxious Manhattan homemaker (there’s 1967 for you!) who’s not-quite-on-the-verge of a nervous breakdown, though she isn’t doing all that well, either. Married to a needling, proto-Yuppie lawyer (Richard Benjamin) who will only drink his ginger ale with cracked ice (not cubed), and the mother to a pair of bratty little girls, Bettina isn’t interested in the class-conscious social climbing with which her husband is obsessed. A distraction comes in the fashionable form of a narcissistic and cynical writer (a darkly appealing Frank Langella), with whom she enjoys some “rolls in the hay”—the kind that her husband provides only when he’s in the mood and with little imagination.

Based on Sue Kaufman’s almost-classic, consciousness-raising bestselling novel from 1967, directed by Frank Perry and adapted for the screen by his then-wife Eleanor Perry not long before they divorced, Diary plays as a comedy-drama while revealing Bettina’s inner feelings and desires. Today, a half-century later, the film’s scenarios and dialogue come off like a period-perfect lampooning of the Second Wave feminism-flavored fiction that flooded the market in those years. But Benjamin and Langella are still fine as caricatures of two very different kinds of men who only want a woman for two things (and one of them involves cleaning). Oscar-nominated Carrie Snodgress, whose performance inspired the song "A Man Needs a Maid" by her soon-to-be lover Neil Young, is the shining star here; she’s focused, occasionally furious, and fraying at the edges even as she discovers that she’s not the only one in New York City getting screwed—and screwing herself—out of happiness and respect.

Oh, wait…it’s Halloween weekend, so let me suggest a late-night date with The City of the Living Dead, a creepy little fright flick from 1960 that you can find for free on YouTube.

Set in the fictional New England village of Whitewood, where witches were burned at the stake three centuries earlier, it follows ill-fated university student Nan who visits the town and checks into the Raven’s Inn to study up on witchcraft and the area’s unholy history. Before too long, she encounters a coven of witches looking to provide the Devil with a human sacrifice or two at the upcoming weekend’s “Hour of Thirteen.” A couple of weeks later, after Nan’s disappearance, her fiancé and her brother head up to Whitewood themselves, only to encounter more of the same and another unholy witch’s holiday on the horizon.

City of the Dead is a British production directed by John Llewellyn Moxey, best known as a prolific television director who helmed one of TV’s greatest horror-mysteries, 1972’s The Night Stalker with Darren McGavin. Shot entirely on the soundstages of England’s venerable Shepperton Studios, City drips with atmosphere—from ghostly village townsfolk to a cross-filled local cemetery to cobwebby basements that coeds shouldn’t be exploring—and the filmmakers get a lot of mileage out of their fog machine, creaky-looking exteriors and shadowy backdrops. The British cast, which includes supporting player Christopher Lee, all trot out their best Northeastern accents as the fog gets even more ominous, as do the eerie, Gregorian-styled choral arrangements by composer Doug Gamley.

Keep your eyes open for a memorable edit between a sacrifice performed on a Satanic altar and the slicing of a creamy birthday cake, a sequence that’s stuck with me ever since I first saw the film on local WOR-TV in the early Seventies. I was eight years old, the film was billed under the U.S. release title of Horror Hotel, and it scared the hell out of me. And that’s what makes for a proper Halloween—now go get your fright on!

Laurence Lerman is a film journalist, former editor of Video Business--Variety's DVD trade publication--and husband to The Insider's own Gwen Cooper. Over the course of his career he has conducted one-on-one interviews with just about every major director working today, including Martin Scorsese, Quentin Tarantino, Clint Eastwood, Kathryn Bigelow, Ridley Scott, Walter Hill, Spike Lee, and Werner Herzog, among numerous others. Once James Cameron specifically requested an interview with Laurence by name, which his wife still likes to brag about. Most recently, he is the co-founder and editor-in-chief of the online review site DiscDish.com.

Comments